In loving memory: a tribute to Kiumars Purahmad

TEHRAN- Today marks the anniversary of your passing, my dear friend Kiumars. Instead of the everlasting lament and regret that are appropriate in their place, I want to recall a memory of your artistic spirit.

One particular line from your film, "The Night Bus," told by a Basiji boy (Mehrdad Sediqian) armed with a single gun escorting thirty-nine enemy prisoners alongside a grumpy elderly driver (Khosro Shakibai) stands out in my memory.

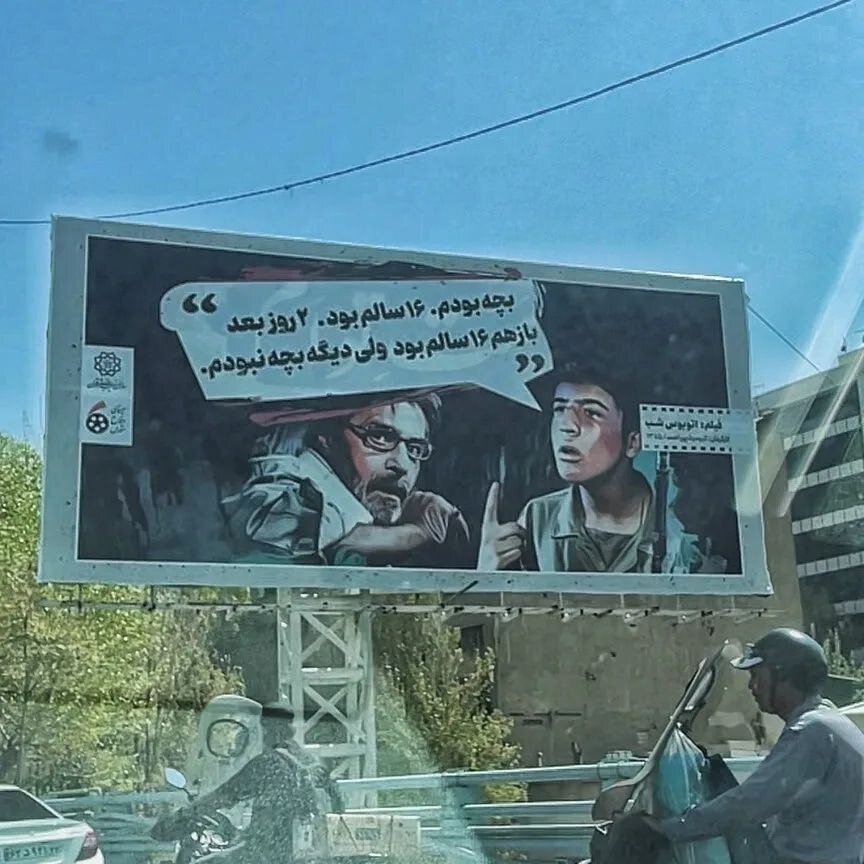

These peculiar yet unforgettable words from your film, which were even featured on the billboards of Tehran, resonate deeply: "There was a war, I was a child I was sixteen. Two days later, I was still sixteen, but I was no longer a child."

These lines were not part of the original narrative of the "Thirty-Nine and One Prisoners" (from the book "City of War Stories") that served as the inspiration for the film. When writing the screenplay and traveling to Abadan one night, this was how I described it to you.

On the day prior to the Iraqi Baath forces' arrival in Zulfaqari, following the fall of Khorramshahr, our neighborhood in the heart of Abadan was viciously bombarded by the enemy's artillery. During this attack, some women and girls from nearby alleys lost their lives or sustained injuries.

I came from the neighborhood mosque to my house at the age of just fifteen, sixteen years old, to bid farewell to my mother and father, who were, along with the rest of the family, preparing to leave the city unavoidably, with the final van of one of the neighbors. I vividly recall that one of my hands idly rested in the pocket of my military pants, while the other gripped a rifle, topped with a bayonet taller than me at the time, with a faint smile lingering on my lips. Perhaps that smile stemmed from the relief of momentarily escaping the impending peril awaiting the remaining members of my family once they stepped outside and went to a safe area outside the fire and war.

My two sisters had already left with my uncle's wife, leaving my mother behind with my aunt and cousin, who had chosen to remain in the city despite the fall of Khorramshahr. With no other options, I too was left with no choice but to leave my family, all of whom were preparing to board the mud-covered blue pickup truck, a precaution taken by our neighbors to evade detection by enemy infantry along the way.

Before climbing into the van, my mother turned to look back at our house and then tearfully beseeched me. I understood from her gaze that she was silently pleading, "You must come too!" Stepping back, I made it clear that I had made the decision to stay behind. As my father closed the van door, he declared, "Your son is becoming a man; he wants to stay." My mother said nothing further, and the van departed.

I entered the empty house with a smile, the only remaining occupants being our belongings. My gaze wandered aimlessly, and suddenly the weapon slipped from my grasp, causing me to collapse to my knees in anguish, crying out and wailing loudly. In that moment, I fully grasped the harsh realities of isolation, loneliness, and abandonment in a city under siege. Overcome with emotion, tears did not fall, yet my hoarse sobs echoed through the empty rooms. Abruptly, it all came to an end. Just as swiftly as the emotions had overwhelmed me, they dissipated; I dried my eyes, retrieved my weapon, and exited the house, leaving it behind forever, embarking on an eight-year journey of unrelenting conflict that would irrevocably change me.

These words, which you have transcribed from my memories, encapsulate the essence of my experience: "There was a war, I was a child, I was sixteen. Two days later, I was still sixteen, but I was no longer a child."

Regrettably, I must share with you an even graver truth, Dear Kiumars that perhaps these same sentences unfortunately whisper to thousands of children like me, even now in Gaza, in Arabic, to each other in reality. Just like me forty years ago on that day. As Habib has not yet returned to his childhood home. Just as you yourself will never return to us. Anyway, Dear Kiumars, may your soul rest in peace, my eternal companion.

Leave a Comment